Aztlán, the mythical place of origin of the Aztec people of Mexico became a political “nation” at the height of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. As an act of defiance, Chicanismo took a term of denigration and declared instead the proud identity of Mexicans in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, California, and Nevada, lands that the U.S. took from Mexico in 1848. But the term and “el Movimiento” ignored activist Latina/os outside the Southwest.

Aztlán, the mythical place of origin of the Aztec people of Mexico became a political “nation” at the height of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. As an act of defiance, Chicanismo took a term of denigration and declared instead the proud identity of Mexicans in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, California, and Nevada, lands that the U.S. took from Mexico in 1848. But the term and “el Movimiento” ignored activist Latina/os outside the Southwest.

“Beyond Aztlán” refutes that limitation as well as challenging any essentialist “Chicano” identity. Curator Professor Lauro H. Flores, Director of Ethnic American Studies at the University of Washington points out that Spanish artists accompanied the earliest explorers to the Northwest in the late 18th century, an area originally known at Nueva Galicia. Atanasio Echeverría y Godoy created 200 drawings on an expedition with Botanist/explorer José Mariano Moziño. A few facsimiles of his detailed work are included in this exhibition.

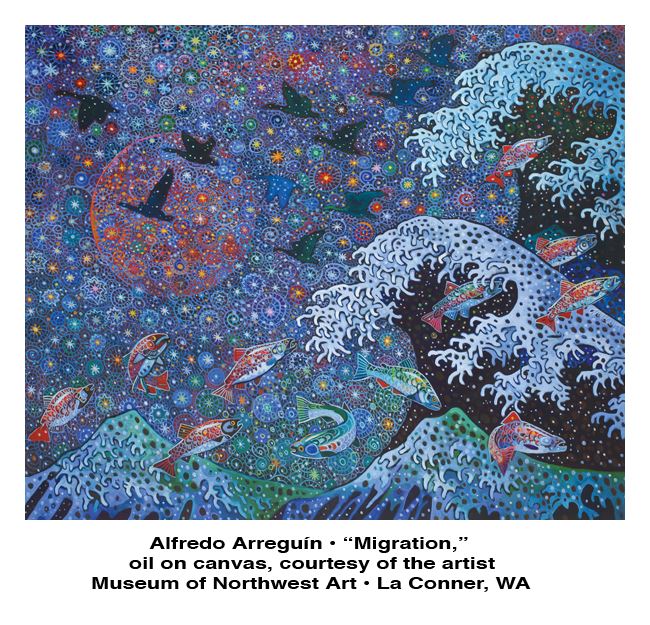

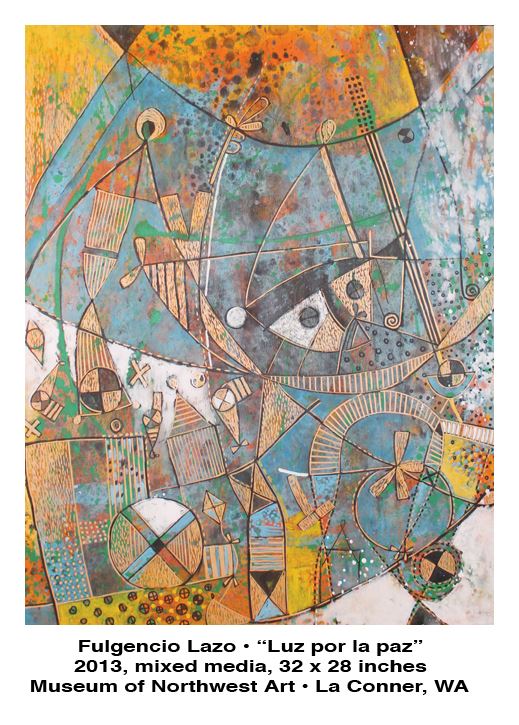

The exhibition then leaps forward to the freely painted abstract expressionist paintings by Boyer Gonzalez Jr., chair of the School of Art at the University of Washington from 1954 to 1979. Alfredo Arreguín took classes with Boyer, but turned in a different direction, based on his exposure to Japanese art and his love of the complex natural world of the jungle. Arreguín immerses portraits and animals in intricate layers of color and pattern. “Migration,” his newest work, incorporates salmon flying through the sea as a wall of waves (inspired by Hokusai) descends on them. Arreguín might be offering a metaphor for the current challenges of human migration. Another variant of abstraction by Fulgencio Lazo links geometric abstraction with indigenous symbolism. His palette of oranges, reds, and blue/greens invokes the warmth of his native Oaxaca where he lives part of the year.

The exhibition then leaps forward to the freely painted abstract expressionist paintings by Boyer Gonzalez Jr., chair of the School of Art at the University of Washington from 1954 to 1979. Alfredo Arreguín took classes with Boyer, but turned in a different direction, based on his exposure to Japanese art and his love of the complex natural world of the jungle. Arreguín immerses portraits and animals in intricate layers of color and pattern. “Migration,” his newest work, incorporates salmon flying through the sea as a wall of waves (inspired by Hokusai) descends on them. Arreguín might be offering a metaphor for the current challenges of human migration. Another variant of abstraction by Fulgencio Lazo links geometric abstraction with indigenous symbolism. His palette of oranges, reds, and blue/greens invokes the warmth of his native Oaxaca where he lives part of the year.

Among the realist artists, ardently feminist and anti-capitalist Cecilia Alvarez fills her portraits with specific but, cloaked, references. “La Rumbera Mayor,” the artist explains, “speaks of the mixing of the races/cultures creating a power image of a woman of color. Also, she is the symbol of creating healing music”.

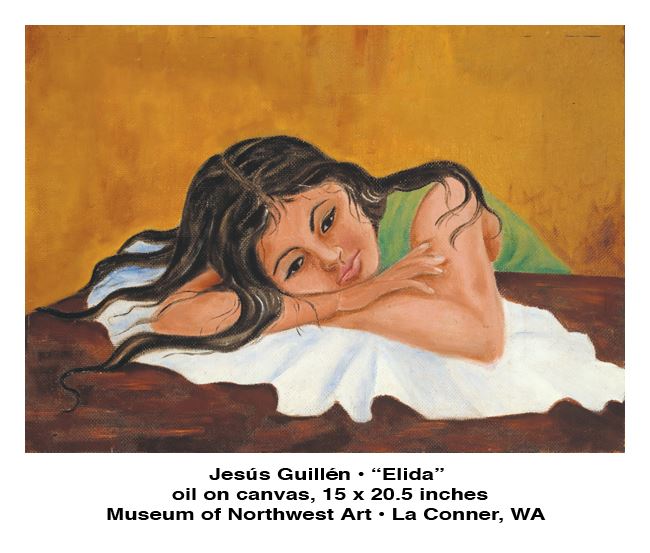

The tight details in Alvarez’s paintings starkly contrast to the soft edges in the paintings of Jesús Guillén. After a full day of backbreaking work in the fields, he sympathetically painted representations of farmworkers. One of his daughters Angelica Guillén organized a two night poetry festival “¡Xicanismo Afire!” that accompanied the opening of the art exhibit. Particularly poems like those of Ramon Ledesma, who grew up as a migrant worker, resonated with the visual art.

The tight details in Alvarez’s paintings starkly contrast to the soft edges in the paintings of Jesús Guillén. After a full day of backbreaking work in the fields, he sympathetically painted representations of farmworkers. One of his daughters Angelica Guillén organized a two night poetry festival “¡Xicanismo Afire!” that accompanied the opening of the art exhibit. Particularly poems like those of Ramon Ledesma, who grew up as a migrant worker, resonated with the visual art.

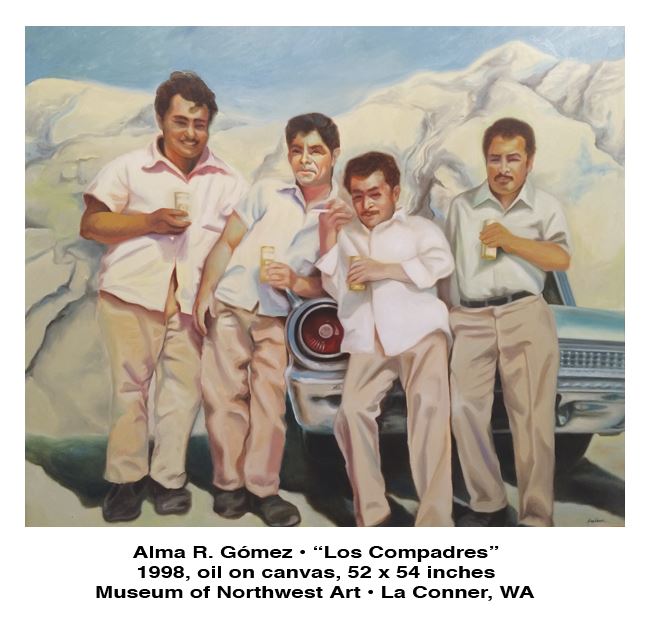

Alma R. Gómez’s large paintings celebrate her family with indigenous and natural symbolism in “Las Tortolitas del Rio Grande” and with matter of fact everyday details in “Los Compadres.” As in Gómez’s paintings, many poets emphasized the crucial importance of family for farmworkers.

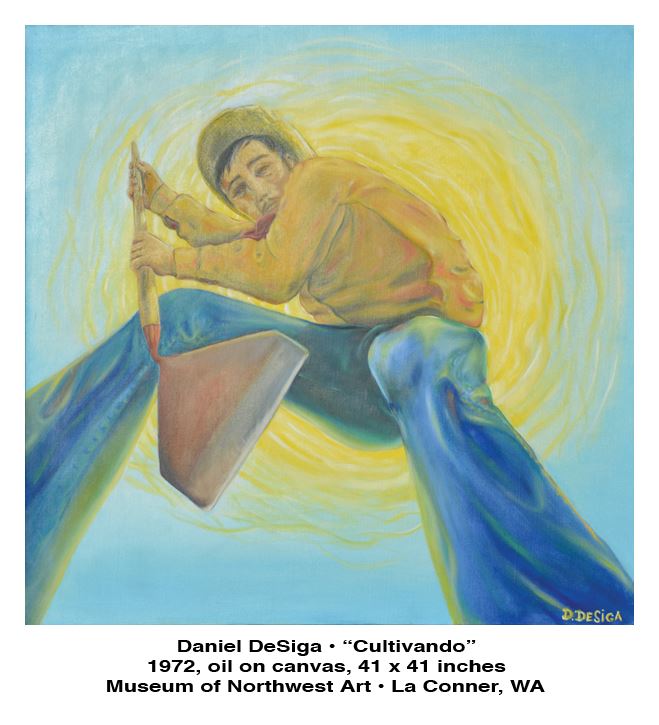

In another approach to realism, Daniel DeSiga’s “Cultivando,” places us on the ground looking up at the farmworker, bathed in a halo-like blazing sun, as his hoe thrusts toward us.

In another approach to realism, Daniel DeSiga’s “Cultivando,” places us on the ground looking up at the farmworker, bathed in a halo-like blazing sun, as his hoe thrusts toward us.

Other artists affiliate with Surrealism. Arturo Artorez’s undecipherable images provoke discomfort; José Luis Rodriguez Guerra’s dark palette and dramatic lighting evoke a supernatural world; and the pencil drawings by Jesús Mena Amaya suggest the disjunctions of automatic drawing.

Two photographers experiment with their media. Paul Berger plays with avant-garde irony in his “Double RR Puppet” (referring to Ronald Reagan) and Daniel Carrillo explores nineteenth century techniques like daguerreotype and ambrotype.

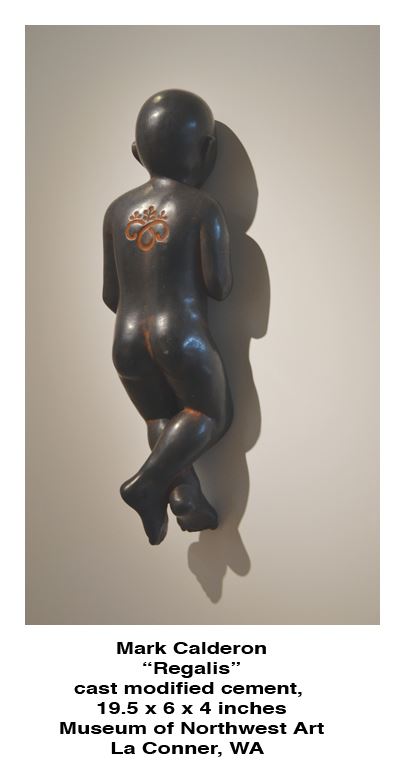

Finally, three sculptors, spanning several decades, range from humorous to mysterious. Rubén Trejo’s “Cheech” has a bomb for a face (suggesting the comedian’s explosive personality). In contrast, “La Llorona,” (The Weeping Woman), represents an iconic Mexican figure of a mother crying for her lost children. The twisting green metal and painted wood combines a modernist base with a jalapeño-like body and a hot red pepper head that emphasizes her agony. Cast modified cement sculpture by Mark Calderon suggests deep poignancy in “Regalis,” a child’s torso facing the wall. The youngest artist in the exhibition, George Rodriguez creates stoneware sculptures that combine humor, realism, kitsch, history, the past, and the future.

Finally, three sculptors, spanning several decades, range from humorous to mysterious. Rubén Trejo’s “Cheech” has a bomb for a face (suggesting the comedian’s explosive personality). In contrast, “La Llorona,” (The Weeping Woman), represents an iconic Mexican figure of a mother crying for her lost children. The twisting green metal and painted wood combines a modernist base with a jalapeño-like body and a hot red pepper head that emphasizes her agony. Cast modified cement sculpture by Mark Calderon suggests deep poignancy in “Regalis,” a child’s torso facing the wall. The youngest artist in the exhibition, George Rodriguez creates stoneware sculptures that combine humor, realism, kitsch, history, the past, and the future.

In short, this group exhibition brings together some of the many dynamic artists among contemporary Mexican/Chicana/o art in the Northwest. It reveals the diversity in life experiences as well as in style, media, background, training, and expression within the limiting label “Chicano” or “Mexicano.” The last museum exhibition of “Chicano” art in the Northwest was over 30 years ago. Let us hope that “Beyond Azteca” stimulates new exhibitions of these exciting artists sooner than that.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D., art historian, art critic, curator, and activist. She continues to address politically engaged art on her blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com. As a curator, her focus is art about immigration, migration, and detention.

“Beyond Aztlán: Mexican and Chicana/o Artists in the Pacific Northwest” is on view through June 12, Sunday and Monday from noon to 5 P.M. and Tuesday through Saturday from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. at the Museum of Northwest Art, located at 121 South First Street in La Conner, Washington. For more information, visit www.monamuseum.org.